Introducing Selma

Introducing Selma

Brian Ward,

Professor in American Studies

It's always a nerve-wracking experience for a professional historian to watch a feature film or television drama that purports to depict real events, particularly if it’s on a topic where we like to claim some expertise. Will the drama get the basic facts and chronology right?; will the on-screen characterisations ring true?; will the film get the clothes and hair right?

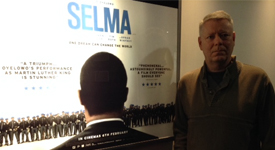

As a historian of the US South and the civil rights movement, all those thoughts were rushing through my mind as I watched the Oscar-nominated Selma for the first time, especially knowing that I had been asked to deliver introductions to the film in Newcastle at special screenings at the Star and Shadow and Tyneside cinemas.

As I explained to those audiences, the good news is that Selma is a powerful, often inspirational film that only occasionally plays fast and loose with the historical record or offers up dubious interpretations of events. The film recounts the story of the historic campaign for Voting Rights in an Alabama city where a mix of white violence, intimidation, and legal chicanery meant that in 1965 only 383 out of a potential black electorate of more than 15,000 were registered to vote. A series of nonviolent demonstrations met with brutal, sometimes lethal white resistance from local law enforcement agencies and vigilante groups. The protests culminated in the events of Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965, when state troopers, some of them mounted on horseback, beat and tear-gassed marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge as they tried to walk to Montgomery, the state capital, to protest before Alabama governor and segregationist icon George Wallace. A march two days later led by Martin Luther King was aborted on what became known as Turnaround Tuesday, but a third march, attracting as many as 25,000 supporters from around the nation, eventually made it to Montgomery.

These events helped to keep the issue of voting rights in the public eye and on the political agenda. On August 6, 1965, President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law. By the time of the Alabama primary elections in 1966, more than 10,000 African Americans in Selma were on the voting rolls. They immediately used that power to remove from office the vicious racist sheriff Jim Clark, one of the stalwarts of segregation who stalks the film, determined to keep blacks in their place by any means necessary. This pattern was repeated across the South, transforming US politics in the process. Whereas there were fewer than 500 black-elected official in the country in 1965, today there are more than 10,500 – and one of them is president of the US!

Good though Selma is, however, there were moments which prompted a raised eyebrow. Some were relatively minor crimes against historical accuracy, often perpetrated in the name of dramatic effect. For example, the film gives the false impression that the Ku Klux Klan’s bombing of the 16th Avenue Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four young black girls preparing for Sunday School, happened after Martin Luther King had received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964: the atrocity actually occurred in September 1963. Similarly, the film shows a tape recording of King with another woman arriving at the family home during the spring 1965 Selma protests, when the FBI had actually sent it a year earlier in an effort to destroy King's marriage and undermine his leadership.

The sharpest intakes of breath, however, came whenever LBJ appeared on screen. Selma misleadingly paints the president as an extremely reluctant supporter of Voting Rights legislation. In fact, LBJ had argued for a separate Voting Rights Act soon after assuming the presidency in late 1963. He needed no convincing of the urgent need for federal action to support and protect black votes in local, state, and national elections -- not least because he saw the Democratic Party as the main political beneficiary of a bigger black electorate. But he also had a firm moral commitment to the vote and saw no reason to wait until after the implementation of his "War on Poverty" programmes as the film suggests.

Now, it is not that hard to find fault with a man who was vain, paranoid, prone to bullying, escalated the catastrophic war in Vietnam rather than risk his own political future, and liked to take official meetings while sitting on the toilet, without having to misrepresent his commitment to securing and protecting black electoral participation. Yet, the film goes out of its way to minimize any credit LBJ might get for helping to restore black voting rights. To further tarnish LBJ's record, Selma even implies that he authorized FBI wire taps on Martin Luther King and other black leaders, which was actually done by Attorney General Robert Kennedy a few years earlier.

So why did director Ava Duvergny choose to make LBJ such an unwilling or dilatory supporter of voting rights? Within the logic of the film, LBJ is clearly sacrificed for dramatic effect. Hollywood loves a good conversion story. In Selma, the Movement creates a crisis and a sense of righteous indignation which finally moves a dithering President to recognize and respond to the urgent need for federal action. It's all very neat and clean; a black and white morality tale. Unlike in a more nuanced historical account of LBJ's attitude to the civil rights movement, such as Freedom's Pragmatist by my Northumbria University colleague Professor Sylvia Ellis, there are no shades of grey here (By the way, I'm still waiting for the invitation to share my expertise on the contents of that film with local cinema audiences...)

I think the caricaturing of LBJ also has a lot to do with a laudable desire to put African Americans front and centre in Selma. This is both historically and morally correct. Black people were the heart and soul of the civil rights movement and, in large measure, created the climate of concern, the widespread public outrage against segregation and disenfranchisement and the violence used to sustain them, which compelled many whites and northern politicians to support change.

Duvergny’s desire to make sure that African Americans are portrayed as active in the creation of their own history offers a valuable corrective to the way they have been portrayed in several other Hollywood films. In Mississippi Burning, for example, the FBI - an organization which, as Selma clearly shows, was far more of a hindrance to the Movement than a help - arrive like the cavalry in some old Western movie to save the day while the black population of Mississippi are virtually mute and impotent. How refreshing, then, to find African Americans in Selma as the main leaders, movers and shakers of the protests. Compare that to the depiction of African Americans in other recent films such as The Help, The Butler, and 12 Years a Slave. All these films had their virtues - well, maybe not The Help, which just about managed to ignore the black-led civil rights movement in Mississippi taking place during the period and in the place where the film is set. But domestic servants, butlers and slaves hardly exhaust the range of contributions that African Americans have made to American history. Selma offers a far more positive and empowering vision of black history.

Of course, the dominant figure in Selma is Martin Luther King, Jr. For those who know the history of the Movement, there is a certain irony in this. Selma makes King the centrepiece of a film about a campaign to which he arrived relatively late and in which he played a very limited role. Amelia Boynton had been campaigning for voting and civil rights in the city as head of the Dallas County Voters League since the 1930s; young activists from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee had been organizing there for several years before King appeared. In fairness, both Boynton and SNCC workers are portrayed in Selma, which is actually rather good at showing the tensions over tactics and timings within and between various civil rights organizations. Still, the fact is that King actually missed the main event in Selma, the brutal attacks of Bloody Sunday. Perhaps this focus is inevitable. It might have been hard to find funding, or even an audience, for the film if King had not been central to it. Everyone is drawn to King like moths to a flame, but sometimes at the expense of acknowledging the extraordinary ordinary people who, as King himself was always quick to acknowledge, actually made the Movement possible.

Finally, I think it important that audiences watching Selma are aware that, because King's family withheld permission to use any of his own words in the film, the magnificent speeches delivered by actor David Oyelowo are cleverly wrought in Selma are cleverly wrought paraphrases and imaginings of things King's actually or might have said. Although a personal letter from King that his wife Coretta reads at one point seems to have been pure invention, such creative sleights of hand help to bring to light an emotional aspect of King's life that historians have been less interested, or less successful, in exploring. Selma works really hard to humanize King, to show his domestic travails, his doubts and human frailties, rather than simply presenting him as some kind of untouchable demi-God. King was in many ways an exceptional figure, yet he made serious errors of judgement in his private life and as a social activist. Ultimately, he seems more -- rather than less -- inspirational when portrayed in Selma as a rounded, if flawed, human being, rather than as some kind of divinity.

Forthcoming Events

If you want to learn more about the US Civil Rights Movement and its connections with Tyneside you may be interested in visiting the Journey to Justice Exhibition which opens on Saturday, April 4, 2015 at the Discovery Museum, Newcastle.

There will also be a special event at the Great North Museum at 7-9.30pm on Friday, April 24 at which Brian Ward (Northumbria University) and Murphy Cobbing (BBC) will discuss Martin Luther King’s historic 1967 visit to Newcastle and its legacy. The event will feature rare footage of King in Newcastle.

For more information on both events please visit: www.journeytojustice.org.uk

Introducing Selma

Introducing Selma